He begins by defining what he calls "the final version" (p. 307):

There is also a "variant version" (p. 307):Il Tarocco di Marsiglia si evolvette in una versione definitiva, prodotta sia in Francia, in particolare a Marsiglia, sia in Svizzera. Non è possibile dire né quando questa versione definitiva abbia preso forma né in quale paese ciò sia avvenuto.

(The Tarot of Marseilles evolved into a final version, produced both in France, especially in Marseilles, and in Switzerland. It is not possible to say when this final version took shape or in what country this happened.)

These days it is more customary to call the two versions "TdMI" and "TdMII", a nomenclature adopted by Thierry Depaulis..Nondimeno, anche un certo numero di carte francesi, in particolare quelle fabbricate a Lione e Avignone, presentano difformità di disegno dalla versione definitiva. La maggior parte di queste difformità rappresenta chiaramente uno stadio di sviluppo del modello anteriore alla versione definitiva.

(Nevertheless, a number of French cards, especially those manufactured in Lyons and Avignon, have differences in design from the final version. Most of these differences clearly represent a stage of development prior to the final version of the model.)

THE TAROT OF MARSEILLE "FINAL" VERSION

Dummett focuses on the "final version" first (p. 308):

Footnote 1 is the most interesting part. It deals with alleged 17th century examples of the "final version". First he discusses a well known one with the notation "Chosson 1672." on the 2 of Coins:Il più antico esempio della versione definitiva del Tarocco di Marsiglia databile con sicurezza è un mazzo del 1709, opera di Pierre Madenié di Bigione 1. Poco dopo, nel 1718, un altro esempio fu realizzato da un fabbricante svizzero, Francois Héri di Soleure (Solothurn) 2. Un altro antico esempio della versione definitiva è un mazzo di Jean Francois Tourcaty figlio, attivo a Marsiglia dal 1734 al 1753, anche se le matrici potrebbero essere state disegnate da suo padre Francois Tourcaty, attivo in [end of 308]

___________________

1. [see below]

2. Esemplari dei mazzi di Madenié e di Héri sono conservati presso lo Schweizerisches Landesmuseum di Zurigo. C’è anche un esemplare del mazzo di Madenié, privo di tutti i trionfi, nel British Museum. Per illustrazioni di questo mazzo, si veda S.R. Kaplan, op. cit., pp. 212 e 315; per illustrazioni del mazzo di Héri, si vedano il catalogo Schweizer Spielkarten. della mostra al Kun-stgewerbemuseum di Zurigo, 1978, n. 142, e S. R. Kaplan, op. cit., p. 317.

(The oldest example of the final version of the Tarot of Marseilles dated with certainty is a deck of 1709, the work of Pierre Madenié of Bigione (1). Soon after, in 1718, another example was made by a Swiss manufacturer, Francois Heri of Solothurn (2). Another early example of the final version is a deck of Jean Francois Tourcaty son, who worked in Marseille from 1734 to 1753, although the matrices may have been designed by his father Francois Tourcaty, active in that city from 1701 to the 1730s.

___________________

1. [see below]

2. 2. Examples of Madenié and Heri packs are stored in the Schweizerisches Landesmuseum in Zurich. There is also a copy of the deck by Madenié, devoid of all the triumphs, in the British Museum. For illustrations of this deck, see S. R. Kaplan, op. cit. [see below], p. 212 and 315; for illustrations of the Heri,deck, see the catalog Schweizer Spielkarten. of the exhibition at the Kunstgewerbemuseum of Zurich, 1978, n. 142, and S. R. Kaplan, op. cit., p. 317.)

Actually, I am not sure it is strange. I once attempted to say, based on Kaplan Vol. 2, p. 211, that the French firm of Grimaud began business in 1748. http://www.tarotforum.net/showthread.php?p=2802307&highlight=Grimaud#post2802307 and posts following). Kaplan Martine Baudin of the J. M. Simon Company (current owner of Grimaud) to that effect. But in fact it was a previous producer, Arnauld, who started in 1748; Grimaud bought the Arnauld company in 1848 and established Grimaud in 1851. When a card maker takes over another's business, he considers that the company started whenever the original business started. He changes the name to his own but does not change the date on the designs he has inherited. In the U.S., a company can be "founded" in such a such a year even though it has gone through a number of owners--however the convention is that the name should stay the same. In France, among cardmakers at least, it is not like that. As to what Grimaud actually did with his 2 of Deniers, I don't know. I haven't found a historic Grimaud Tarot de Marseille to check. But I do know that on my 1969 Grimaud Grand Etteilla (put out by J. M. Simon) it says "Avec les Compliments de Grimaud France manufacteurs de Cartes a Jouer depuis 1790". whereas Corodil on Aeclectic informs me, surely correctly,1. Stuart R. Kaplan, in The Encyclopedia of Tarot, Vol, II, New York, 1986, pp. 310 e 312, ha preteso che un mazzo di Francois Chosson, un altro esempio tipico della versione definitiva, sia del 1672. È vero che la banderuola dei 2 di Denari reca, a quanto pare, la scritta «Francois chosson 1672»; è difficile interpretare la data altrimenti che 1672. Nondimeno, secondo Joseph Billioud, 'La Carte à jouer, une vieille industrie marseillaise', Marseille, n. 34-5, 1958, e l’elenco di maestri cartai francesi di H.-R. D’Allemagne, Les Cartes à jouer, Parigi, 1906, Francois Chosson è documentato come attivo a Marsiglia fra il 1734 e il 1736. Sul trionfo VII e sul 2 di Coppe compaiono le iniziali G S. Secondo D’Allemagne, un maestro cartaio Guillaume Sellon era attivo a Marsiglia dal 1676 al 1715, ed è possibile che egli disegnasse queste carte nel 1672. In tal caso il Tarocco di Marsiglia avrebbe raggiunto la sua forma definitiva nel penultimo quarto del Seicento; ma sembra strano il solo cambiamento del nome del fabbricante senza quello della data.

br /> (1. Stuart R. Kaplan, in The Encyclopedia of Tarot, Vol. II, New York, 1986, p. 310 and 312, has proposed that a deck of Francois Chosson, another typical example of the final version, was in 1672. It is true that the 2 of Coins bears, apparently, the words 'Francois Chosson 1672'; it is difficult to interpret the data otherwise than 1672. Nevertheless, according to Joseph Billioud, 'La Carte à jouer, une vieille industrie Marseillaise', Marseille, n. 34-5, 1958 and the list of French master cardmakers of H.-R. D’Allemagne, Les Cartes à Jouer, Paris, 1906, Francois Chosson is documented as being active in Marseille between 1734 and 1736. On the seventh triumph and the 2 cups are the initials G S. According to D'Allemagne, a master cardmaker Guillaume Sellon was active in Marseille from 1676 to 1715, and it is possible that he had designed these cards in 1672. In this case, the Tarot of Marseilles would reach its final form in the penultimate quarter of the seventeenth century; but it seems strange to just change the name of the manufacturer without the date.)

There is a thread on THF on the Chosson dating, http://tarothistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=53, which has a picture of the relevant card. As Ross Caldwell points out there, the "Chosson" appears to be different from the other lettering on the card; thus he likely o bought the plates from a previous producer and put his name in place of the original name. Another post of Ross's (http://forum.tarothistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=53&p=458&hilit=initials#p458) speaks to the initials "GS" in the middle of the Chariot card.Baptiste Paul Grimaud went to Paris at the beginning of the years 1840, he was then 23 years old. He creates Grimaud & Cie on the 12 June 1851 after he bought Arnould in 1848.

Guilhen Sallonetz is mentioned with someone who seems to be his father or brother, Jacques Sallonetz, at the same time (1662).The difficulty, as Ross points out, is how to account for that style of Tarot de Marseille so early.

Further in the list, there are others - Guillaume Sellon (1676-1715), Jacques Sellon (1676-1708), along with Jean-François Sellon (1676-1688) Antoine Sellon (1713-1715), and Claude-François Sellon (1730) - all in Marseille.

I am guessing that the names Sallonetz and Sellon are two forms of the same name, one in Provençal, and one in French. "Guilhen" is a Provençal form of "Guillaume" (although "Jacques" is pure French in both cases). So we are dealing with a family business that is attested from 1662-1730. Perhaps Chosson bought it after the final Sellon retired.

There is a problem stylistically though. This Tarot de Marseille is "TdMII" by Depaulis' taxonomy - the Cupid is going to the right as is not blindfolded, the figures in the Sun are two little boys, not a boy and a girl (or youths of opposite gender), the figure in the World is also a "sexy" female, etc. (like in Conver).The question is whether the "TdMII" can be reasonably expected that early, 1672. The problem is that the early printed cards of the Marseille style, as evidenced by the Cary Sheet, of c. 1500 Milan, and the cards found in the Sforza Castle during some remodeling, from 1499 to around 1600, reflect the TdM I imagery rather than the TdMII, as we shall see when we get to those cards (his next chapter). What evidence is there for a TdMI style so early? I am not sure there has to be any. 1672 is not so far in advance of 1709. The first known TdMII deck is c. 1650, Noblet, after which the second is c. 1700 Dodal. That is 50 years. The gap for the TdMI is less than that.

In fact, the style of the TdMII is close to that of Baldini's engravings of sibyls and prophets done in Florence during the 1470s, as Cristophe Poncet has shown in a recent essay, "Un gioco tra profezia e filosofia: i tarocchi di Marsilio" (in Linguuagi degli Cielo, 2012, pp. 254-269). Unlike him, I do not propose that the TdMII was done as early as that. It is just that the more refined style of the TdMII, compared to the TdMI, had been around for a couple of centuries before 1672; it did not have to wait for new developments in the technique of French engraving that did not appear before 1700. Since Poncet's essay is not generally accessible, at least to English-speaking readers, I will include a summary of the relevant parts, with pictures, as an Appendix to this chapter of my blog.

Dummett's footnote 1 also describes another allegedly 17th century deck:

I have not been able to find pictures of these cards.Il Musée Paul Dupuy di Tolosa possiede un foglio non tagliato che presenta dodici figure, comprese la Regina di Denari, i Cavalieri di Coppe e Denari, e tutte e quattro figure di Spade, Il catalogo La Carte à jouer en Languedoc des origines à 1800 della mostra allestita al Musée nel 1971, sezione (1), 'Toulouse', n. 8, lo classifica come opera di un anonimo fabbricante di Tolosa del XVH secolo. La presenza delle Regine garantisce che il foglio era per un mazzo di tarocchi e i disegni delle figure ci permettono di supporlo un Tarocco di Marsiglia: tutte recano le loro denominazioni scritte in fondo alla carta. Tuttavia, la datazione è incerta. Il catalogo fa riferimento a un articolo di B. Dusan, ‘Cartes à jouer anciennes’, Revue archéologique du Midi, Voi. II, 1869, p. 120.

(The Musée Paul Dupuy in Toulouse has an uncut sheet that presents twelve figures, including the Queen of Coins, the Knights of Cups and Coins, and all four figures of Swords, The catalog La Carte à jouer en Languedoc des origines à 1800 of the exhibition at the Museum in 1971, section (1), 'Toulouse ', n. 8, ranks it as the work of an unnamed manufacturer in XVIIth century Toulouse. The presence of Queens ensures that the sheet was for a deck of tarot cards and the depictions of the figures allow us to suppose a Tarot of Marseilles: all bear their names printed at the bottom of the card. However, the date is uncertain. The catalog refers to an article by B. Dusan, 'Cartes à jouer anciennes', Revue archéologique du Midi, Vol II, 1869, p. 120.)

THE "VARIANT' VERSION OF THE TAROT OF MARSEILLE

Dummett gives a long description of the standard features of the "final" version, which I will skip, because this version is well known. He then indicates deviations from this standard. Decks that have a preponderance of these features are what he calls the "variant" version (p. 316):

Then he describes the oldest examples of the "variant" (p. 318). Here he refers to three particular decks, the Noblet, the Dodal, and the Payen. The Noblet triumphs are at http://www.tarot-history.com/Jean-Noblet/index.html. Flornoy on that site dates the cards to c. 1650, while the documentation indicates 1659 as the earliest for him as a master cardmaker. I do not know why Flornoy has the earlier date. The c. 1701 Dodal triumphs are at http://www.tarot-history.com/Jean-Dodal/. The 1713 Payen truimphs are at http://www.tarot.org.il/Payen/. There has been discussion since Dummett about the relationship between these two card makers, but I cannot recall where. They are almost identical:Ci sono molti esempi del Tarocco di Marsiglia conformi in tutti i dettagli alla descrizione precedente. Le due più importanti delle suddette variazioni dalla sua forma definitiva sono relative ai trionfi VI e XXI (l’Amore o l'Innamorato e il Mondo). Nella variante del VI, Cupido vola dalla parte destra della carta, con angolazione discendente, cosicché lo vediamo di spalle, anziché di fronte, anche se vediamo ancora il suo viso. Cupido porta una fascia intorno al capo, la quale in certi mazzi gli benda gli occhi. La figura del Mondo (XXI) è più tozza di quella della versione definitiva, e non ha la gamba sinistra incrociata dietro alla destra; il ginocchio sinistro è piegato molto leggermente. Non indossa la sciarpa, ma ha un mantello, aperto, gettato sulle spalle; le reni sono coperte da una cintura di foglie, e la mano sinistra, che regge un bastoncino, non è sollevata. Questi due tratti — le forme dei trionfi VI e XXI — sono senza dubbio anteriori ai tratti corrispondenti della versione definitiva.

Altre variazioni che accompagnano spesso queste due, ma si trovano anche in loro assenza, sono le seguenti:

(1) ci sono ‘goccioline’ sul Giudizio (trionfo XX), simili a quelle che compaiono sempre sul XVIHI e sul XVHI.

(2) Il fulmine sul XVI proviene da un quadrante nell’angolo della carta.

(3) Sul XV compaiono occhi sulle ginocchia del Diavolo, e un volto sullo stomaco; ha le reni cinte da un perizoma, ma le gambe sono dello stesso colore del torso.

(4) Il Papa (V) non tiene nella mano sinistra una triplice croce, bensì una verga sormontata da un globo e da un vessillo; ci sono tre cardinali.

(5) I Fanti non presentano, in basso, una scritta con i loro titoli.

Tutte queste variazioni sono probabilmente anche anteriori ai tratti corrispondenti della versione definitiva. Benché i mazzi che non rappresentano quella versione non siano di un tipo altrettanto rigido, ma presentino spesso una scelta di tratti alter-[enf of 317]nativi, si può parlare di una variante della versione definitiva, comprendente tutti i mazzi che riuniscono parecchie delle variazioni suddette; l’espressione ‘versione variante’ si userà d’ora in avanti in questo senso. L’inizio del XVIII secolo sembra essere uno stadio di transizione nell’evoluzione del Tarocco di Marsiglia. Nacquero nuove forme e i fabbricanti scelsero ora queste, ora quelle.

(There are many examples of the Tarot of Marseilles that conform in all details to the description above, The two most important of these changes in its final shape are related to triumphs VI and XXI (Love or the Lover and the World). In the variant of the VI, Cupid flies from the right side of the card, with downward angle, so that we see him from behind, instead of in front, although we still see his face. Cupid wears a band around his head, which in some decks blindfolds him. The figure of the World (XXI) is more stocky than the final version, and did not cross her left leg behind her right; the left knee is bent very slightly. It does not wear the scarf, but it has an open mantle thrown over her shoulders; the abdomen is covered by a girdle of leaves, and her left hand. not raised. holds a stick. These two sections - the forms of triumphs VI and XXI - are undoubtedly older than the corresponding sections of the final version.

Other changes that often accompany these two, but are also in absence, are as follows:

(1) there are 'droplets' on Judgment (triumph XX), similar to those that always appear on XVIII and XVIIII.

(2) The lightning on XVI comes from a quadrant in the corner of the card.

(3) On XV eyes appear on the knees of the Devil, and a face on the stomach; has the abdomen enclosed by a thong, but the legs are the same color as the torso.

(4) The Pope (V) does not hold in his left hand a triple cross, but a rod surmounted by a globe and a banner; there are three cardinals.

(5) The Jacks do not have at the bottom an inscription with their titles.

All of these variations are probably also older than the corresponding sections of the final version. Although the decks that do not represent that version are not of an otherwise rigid type, these often present a choice of alternative features, if one can speak of a variant of the final version, including all the packs that combine several of these variations; the expression 'variant version' will be used henceforth in this regard. The beginning of the eighteenth century seems to be a transitional stage in the evolution of the Tarot of Marseilles. There came new forms, and manufacturers chose now these, now those.)

I need to point out that this characterization of the differences between the "final" and the "variant" is somewhat misleading in that there are also variations in the "variant". Dodal's name for the Popess is "La Pances". i.e. "The Belly" or "The Paunch", according to Jean-Michel David, discussing this name, suggesting to him a particular interpretation of the card, i.e pregnancy (Reading the Marseille Tarot. a Self-Paced Course, in Google Books, p. 74). Noblet, like the Minchiate, has a man and a woman on the Sun card--but their postures are more like the "standard" model in Noblet than in Minchiate. In Dodal the two people are two boys, as in the "final". Also, the Noblet Pope does not have three cardinals, nor a staff with a globe or a banner, but rather a bishop's crozier. There are many other small variations. These details may be important in tracing the development of the Marseille out of the uncut Cary Sheet and the cards that were found in Milan, which he will discuss in the next chapter.L’unico esempio del Tarocco di Marsiglia sicuramente databile al XVII secolo è un mazzo di Jean Noblet, un fabbricante la cui attività a Parigi fra il 1659 e il 1664 è attestata dagli archivi6. Questo mazzo è di dimensioni eccezionalmente piccole (mm. 92 x 55). Il solo esemplare sopravvissuto, cui mancano soltanto cinque carte numerali di Spade, si trova nella Bibliothè-que Nationale di Parigi; il nome del fabbricante è stampato sulla banderuola a forma di S del 2 dì Denari e sul pannello del 2 di Coppe. Come indicano i trionfi VI e XXI, il mazzo rappresenta la versione variante piuttosto che quella definitiva, che forse non era ancora nata; un tratto insolito è la scritta «la mort» sul trionfo XIII.

Oltre al mazzo di Noblet, uno dei più antichi della versione variante è opera di Jean Dodal di Lione, attivo in quella città dal 1701 al 1715. Questo mazzo, un esemplare del quale è alla Bibliotheque Nationale e un altro al British Museum, reca su parecchie carte la scritta «f.p. le trenge», cioè «faits pour Lé-trange» (fatto per l’esportazione). Nel mazzo di Dodal, come in parecchi altri, il Matto porta la scritta «le fol» anziché ‘le mat’. Perlomeno nel XVIII e XIX secolo il Matto era sempre chiamato ‘il Folle’ dai giocatori piemontesi e 'le Fou’ da quelli savoiardi. Sembra probabile, dunque, che il mazzo di Dodal fosse destinato alla Savoia; ma non possiamo concludere che tutti i mazzi nei quali il Matto porta la scritta «le fol» o «le fou» avessero la stessa destinazione. Un tale mazzo, che esemplifica perfettamente la versione variante del Tarocco di Marsiglia, è quello prodotto nel 1713 da Jean-Pierre Payen (1683-1757). Payen nacque a Marsiglia, ma si stabilì nel 1710 ad Avignone, dove rimase fino alla morte.

(The only example of the Tarot of Marseilles definitely dated to the seventeenth century is a deck of Jean Noblet, a manufacturer whose business in Paris between 1659 and 1664 is attested by the archives (6). This deck is exceptionally small sized (92 x 55 mm). The only surviving example, lacking only five pip cards of Swords, is in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris; the manufacturer's name is printed on a banderole in the shape of an S on the 2 of Coins and a panel on the 2 of Cups. As illustrated by triumphs VI and XXI, the deck is the variant version rather than the final one, which perhaps was not yet born; an unusual feature is the inscription "la mort" on triumph XIII.

In addition to the deck of Noblet, one of the oldest in the variant version is the work of Jean Dodal of Lyon, active in that city from 1701 to 1715. This deck, one copy of which is in the Bibliotheque Nationale, and another in the British Museum, bears on several cards marked «f.p. le trenge», that is, “faits pour Lé-trange” (made for export). In the Dodal deck, as in many others, the Fool bears the words "le fol 'rather than 'le mat'. At least in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Fool was always called 'il Folle' by players in Piedmont and ‘le Fou' by Savoyards. It seems likely, therefore, that the Dodal deck was destined for Savoy; but we can not conclude that all the decks in which the Fool bears the words "le fol" or "le fou" had the same destination. Such a pact that perfectly exemplifies the variant version of the Tarot of Marseilles, is one produced in 1713 by Jean-Pierre Payen (1683-1757). Payen was born in Marseille, but in 1710 he settled at Avignon, where he remained until his death.

________________

6. See the catalog Tarot, jeu et magie, Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, 1984 n. 35, pp. 65-6, and H.-R. D'Allemagne, Les Cartes à jouer, Vol II, Paris, 1906, p. 78 and 619.

Dummett says that the "final version" represents a "later stage of development" than that of the "variant". However, as I have said already, the "final" style is very close to that of Baldini in Florence.

It is true that two examples we have of the "variant" come before that of the "final", if we choose to ignore the 1672 date on the "Chosson". But that might be a function of the place that preserved them--Paris and Lyons vs. Marseille--than anything else. It seems to me impossible to say which came first, without a more detailed analysis than Dummett gives in this chapter. However, the Milan cards of the next chapter may be useful in that regard, so I will wait before passing judgment.

The "final version" is remarkably consistent after a certain point: most manufacturers did not choose "now these, now those" features out of a variety of things that came before. However at one point a couple of changes were made, which changed the subjects of two of the cards so drastically that it got called "variation" on the TdM. The resulting deck was repeated many times and got its own name, the "Tarot of Besançon".

THE TAROT OF BESANCON

There is also the Tarot of Besançon, which Dummett finds more "fluid and lively" than either version of the TdM. The main difference is that Juno and Jupiter replace the Popess and Pope. Also, instead of "le Mat", the Fool is "le Fol" and sometmes the Hermit is called "le Capucin". What he says about the origin of the Tarot of Besançon is of some interest. First he reviews where it was made and when (p. 319f):

He working his way gradually toward a conclusion (p. 322f):Nel XVIII secolo, era prodotto in Svizzera, Alsazia e Germania. In Svizzera, Francois Héri di Solothum — il fabbricante dell’esempio del 1718 della versione definitiva del Tarocco di Marsiglia — fabbricò, probabilmente intorno al 1725, un mazzo non datato che esemplificava il Tarocco di Besançon 10. Il più antico mazzo di questo tipo databile con sicu-[end of 219]rezza è opera di Nicolas Francois Laudier di Strasburgo; i nomi del fabbricante e della città sono scritti sul 2 di Coppe e sul 2 di Denari, le iniziali del fabbricante sul 2 di Denari, la data 1746 e il nome dei rincisore (Pierre Isnard) sullo scudo del Carro, e le sue iniziali sul Cavaliere di Spade 11. Un esempio probabilmente più antico fu fabbricato da Johann Pelagius Mayer di Costanza 12. C.P. Hargrave lo datò al 1680, e asserì che Mayer era stato attivo a Costanza nell’ultima parte del XVII secolo 13. Il dottor Max Ruh ha dimostrato che si tratta di un errore: Mayer nacque infatti a Kempten nel 1690, divenne cittadino di Costanza nel 1720 ed è registrato in documenti del 1730 e del 177714. Un altro esempio fu fabbricato da Neumur di Mannheim verso il 1750, e un altro ancora da G. Mann di Colmar, datato 1752 15. Nella seconda metà del secolo, esempi del Tarocco di Besançon, particolarmente di origine svizzera, diventano frequenti.

_________________

10. Si veda il catalogo Schweizer Spielkarten, p. 143.

11. Si veda Tarot, jeu et magie, n. 44, pp. 74-5. Un esemplare completo è nel Musée des Arts et Traditions Populaires di Parigi.

12. Ce ne è un esemplare nel Museo di cane da gioco dell’United States Playing Card Company di Cincinnati, e un altro nella collezione privata dì Albert Field di Astoria, New York City. Per illustrazioni, si vedano Catherine Perry Hargrave, A History of Playing Cards, New York, 1966 (ristampa), p. 259 e di fronte a p. 260, e S.R. Kaplan, The Encyclopedia of Tarot, New York, 1979, p. 136.

13. C.P. Hargrave, op. cit. New York, 1930, pp. 262, 266.

14. Cfr. Tarot, jeu et magie, n. 45, p. 75.

15. Un esemplare del mazzo di Neumur è al British Museum, e uno del mazzo di Mann al Musée des Arts et Traditions Populaires.

(In the XVIIIth century, it was produced in Switzerland, Alsace and Germany. In Switzerland, Francois Heri of Solothum - the manufacturer of the example of 1718 of the final version of the Tarot of Marseilles - made, probably around 1725, an undated deck that exemplified the Tarot Besançon (10). The oldest dating of deck of this type with security is the work of Nicolas Francois Laudier of Strasbourg; the names of the manufacturer and the city are written on the 2 of Cups and 2 of Coins, the initials of the manufacturer on the 2 of Coins, the date 1746 and the name of the engraver (Pierre Isnard) on the shield of the Chariot, and his initials on the Knight of Swords (11). One example was probably the oldest manufactured by Johann Pelagius Mayer of Constance (12). Č.P. Hargrave dated it to 1680, and asserted that Mayer had been active in Constance in the latter part of the seventeenth century (13). Dr. Max Ruh has shown that it is a mistake: in fact, Mayer was born in Kempten in 1690, became a citizen of Constance in 1720, and is recorded in documents of 1730 and 1777 (14). Another example was manufactured by Neumur Mannheim around 1750, and another by G. Mann of Colmar, dated 1752 (15). During the second half of the century, examples of the Tarot of Besançon, particularly of Swiss origin, become frequent.

____________________

10. See the catalog Schweizer Spielkarten, p. 143.

11 See Tarot, jeu et magie, n. 44, p. 74-5. A complete example is in the Musée des Arts et Traditions Populaires in Paris.

12. There is a specimen in the Museum of playing cards of the United States Playing Card Company of Cincinnati, and another day in the private collection of Albert Field in Astoria, New York City. For illustrations, see Catherine Perry Hargrave, A History of Playing Cards, New York, 1966 (reprint), p. 259 and facing p. 260, and S.R. Kaplan, The Encyclopedia of Tarot, New York, 1979, p. 136.

13. C. P. Hargrave, op. cit.. New York, 1930, pp. 262, 266.

14..See Tarot, jeu et magie, n. 45, p. 75.

15. A copy of a deck of Neumur is in the British Museum, and one of the deck of Mann at the Musée des Arts et Traditions Populaires.

That the tarot spread from French-speaking to German-speaking areas is evident from the fact that in Germany the tarot invariably had French titles.I fabbricanti di carte alsaziani non servivano solo la loro zona, ma esportavano anche in Germania; naturalmente, l’Alsazia era divenuta parte della Francia solo nel 1648. Attraverso lo studio delle aree svizzere in cui erano prodotti mazzi del Tarocco di Marsiglia e del Tarocco di Besangon, Sylvia Mann ha dimostrato che è molto probabile che il primo fosse prodotto [end of 322] per i Cantoni di lingua francese e il secondo per quelli di lingua tedesca. Inoltre, si conoscono pochissimi esempi tedeschi di veri e propri Tarocchi di Marsiglia, poiché in Germania i giocatori si servivano soprattutto del Tarocco di Besangon. Sembra pertanto che fossero i cattolici df lingua tedesca ad avere delle riserve sulla presenza del Papa e della Papessa e a fornire quindi l’occasione per l’invenzione del cosiddetto Tarocco di Besançon.

(The manufacturers of Alsatian cards not only served their area, but also exported to Germany; of course, Alsace had become part of France only in 1648. Through the study of the areas in which the Swiss areas produced Marseilles Tarot decks and the Tarot of Besancon, Sylvia Mann has shown that it is very likely that the first were produced [end of 323] for the French-speaking cantons and the second for those of the German language. Besides, we know very few examples of real German Tarot de Marseille, as in Germany, the players made use mainly of the Tarot of Besançon. It seems, therefore, that they were German Catholics having reservations about the presence of the Pope and of the Popess, thus providing an opportunity for the invention of the so-called Tarot of Besançon.)

But what Dummett says about the reason why Juno and Jupiter substituted for the Popess and Pope is not very convincing. The Pope and the Popess continued to be used in France, which was militantly Catholic, and some Catholic parts of Switzerland for centuries without the players having any reservations. Another explanation that has been offered is that the change was made to accomodate Protestants, who would not like to see the hated Pope and his Church on a playing card. But the fact is that up until this time tarot was a Catholic game, almost exclusively. A likelier explanation than either is that the authorities had reservations about the Pope and the Popess, in areas where substantial numbers of both Catholics and Protestants lived together. Their presence would offer Protestants a chance to ridicule Catholicism. and no doubt lead to brawls in the taverns. It is only because of the presence of Protestants, in areas where the authorities were Catholic, that the Pope and Popess are objectionable.

This is in fact the explanation offered by Thierry Depaulis in his study of the Tarot of Besançon ("When (and how) did Tarot reach Germany?", The Playing Card, Vol. 39, No. 2, pp. 64-79). The French took advantage of the terrible Thirty Years' War to occupy much of Alsace, which the Treaty Treaty of Westphalia granted them, except a couple of cities, including Strassbourg. The French began resettling Alsace with Roman Catholics and also conquered Strasbourg in 168 (Depaulis p. 75). Depaulis argues that there was no tarot in Strasbourg before then (p. 74f). After 1681 Roman Catholics poured into Strasbourg, including, within six years, a card maker (p. 75f), attracted by the large number of French soldiers stationed there. The earlier cardmakers there had been wiped out in the Thirty Years War. All the new ones had French as opposed to Alsatian names. In the early 18th century tarot packs started appearing, all of which lacked the Pope and the Popess. Most had Jupiter and Juno instead, but one, Louis Laboisse, had Spring and Winter (p. 76). The young lady personifying Spring is dressed like the one in a celebrated painting of 1703. Depaulis infers:

Thus it is not unreasonable to imagine that Louis de Laboisse made his Tarot pack soon after his arrival in Strasbourg, around 1710. We may even hypothesize that he first made a standard 'Tarot de Marseille' but that the two trumps, Popess and Pope, met with disapproval by a Roman Catholic authority - Strasbourg, which had been in Protestant hands until 1681, was now under strong Catholic pressure (32) - who demanded that he replaced [sic] the two cards with any other less blasphemous figures. De Laboisse chose "Le Printemps" and "L'Hyver", while his competitors would afterwards switch to Juno and Jupiter. This may well be the origin of the so-called 'Tarot de Besancon'. All Tarot packs made in Strasbourg and later in Colmar follow this type, and we can see that all Latin-suited packs made in Germany also are of the 'Besancon' type.This conclusion is even supported by something Dummett says in the next chapter, talking about decks produced on the Lombard model at the end of the 18th century. One example, marked «in brag» ("in Prague") in the Leber collection, has a note attached. I will let Dummett tell the tale (p.348) :

_____________________

32. Although the French did not manhandle the Protestants, as they were doing in the rest of the country after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685), they were eager to restore the Roman Catholic institutions. This process is known as the "recatholicisation" of Alsace.

What is important about this note, in the present context, is that it is that it is the authorities' attitude that discourages the production of decks with the Popess; the players themselves are not mentioned. Surely their Catholicism was not any more sensitive to slights than those in Marseille around the same time.Sulla nota si legge «Un raro mazzo di Tarocco per il quale il fabbricante fu decapitato a causa di una figura satirica ritrattavi'» e quella che potrebbe essere un’aggiunta posteriore fa specifico riferimento al trionfo n. n, cioè alla Papessa19. Il catalogo attribuisce il mazzo al XVII secolo, ma questo non può essere vero: sicuramente non può essere anteriore al 1760. Né può essere vera la storia dello sfortunato fabbricante: nemmeno nel XVH secolo un sospetto (infondato) di intenzione satirica nei confronti della, Chiesa avrebbe potuto giustificare una punizione così severa. La storia illustra, tuttavia, fino a che estremi si poteva pensare arrivasse l’ostilità per la presenza della Papessa su una carta da gioco. Quella figura sarebbe stata del tutto sconosciuta a giocatori dell’Europa Centrale, che erano abituati al modello del Tarocco di Besancon, con Giove e Giunone al posto del Papa e della Papessa.

_____________________

19 Nell’originale tedesco, la scritta è: «Eine seltne Tarock-Karte, darum der Verfertiger wegen einer dazu gemalten satyrischen Figur enthauptet worden», e di sotto «N°. II / Fig: N°: II».

(On the note is written: "A rare deck of Tarot for which the manufacturer was beheaded because of a satirical figure portrayed'", and what could be a later addition makes specific reference to triumph II, that is, to the Popess (19). The catalog attributes the deck to the seventeenth century, but this cannot be true; surely it cannot be earlier than 1760. Nor can the story of the unfortunate manufacturer be true; not even in the XVIIth century could suspicion (unfounded) of satirical intention in respect to the Church justify a punishment so severe. The story illustrates, however, to what extremes hostility to the presence of the Popess on a playing card came to be thought. That figure would have been completely unknown to players in Central Europe, who were used to the Tarot of Besancon model, with Jupiter and Juno in place of the Pope and of the Popess.

_______________________

19. In the original German, the words are: 'Eine seltne Tarock-Karte, darum der Verfertiger wegen der einer dazu Gemalten satyrischen Figur enthauptet worden', and further on, 'N°. II / Fig N°: II.")

Another confirmation of Depaulis's thesis is that other decks, around this same time in a different border region of France, that between France and what was called "Spanish Netherlands" (modern Belgium) made a different substitution for Pope and Popess, this time Bacchus for Pope and a certain Spanish Captain for the Popess. Dummett discusses these decks in Chapter 14.

It was "Huck" (Lothar Teikemeier) on THF who brought Depaulis's article to my attention. He, however, does not agree with this particular part, saying that the hypothesis is too complicated. Anyone interested in getting his view, which is that the Pope and Popess were omitted to avoid offending Protestants, can read our discussion, starting at http://forum.tarothistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=11&t=1019&start=20#p15183.

APPENDIX: BALDINI AND THE MARSEILLE I AND II STYLES

This part is derived from my post at http://forum.tarothistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=11&t=1004&p=14956&hilit=Baldini#p14956).

Cristophe Poncet's essay, "Un gioco tra profezia e filosofia: i tarocchi di Marsilio" b(in Linguuagi degli Cielo, 2012, pp. 254-269) compares Baldini's "prophets and sybils" series with certain Marseille trumps. Baldini is Florence, not Milan, of course. Poncet starts out (I give the Italian first, then my attempt at a translation):

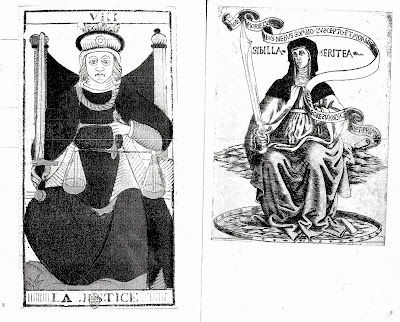

First is the Pope. After my English version, I give his illustration, table 3, and then two TdM I's, Noblet and Dodal, along with the colored TdMII of Conver (already put together for me by http://leefitzsimmons.com/esotericon/index.html; but ignore the card in each series on the far right, which is a modern version of the TdMII):Tra i ventidue trionfi dei tarocchi di Marsiglia, cinque presentano somiglianze straordinàrie con alcune immagini della serie dei profeti e delle sibille di Baldini o di altre stampe create nella stessa cerchia d'incisori fiorentini: la Papessa, il Papa, l'Imperatrice, l'Imperatore e la Giustizia.

(Among the twenty-two trumps of the Tarot of Marseilles, five have similarities with some extraordinary images of the series of prophets and sibyls of Baldini or other prints created in the same circle of Florentine engravers: the Popess, the Pope, the Empress, the Emperor and Justice.)

Il Papa (TAV. 1) è disegnato secondo lo stesso modello del profeta Baruc (TAV. 2): stessa posizione seduta, con il corpo in posizione frontale e la faccia di tre quarti, stesso tipo di mantello lungo; i lineamenti dei volti sono assai simili, in particolare il taglio della barba e dei baffi, la bocca, il mento e il naso. Inoltre, anche alcune differenze testimoniano che una figura dipende dall'altra: se, per esempio, i copricapi sono di specie diverse (una tiara per il papa, un berretto per il profeta), tutti e due sono sormontati da un bottone rotondo che„in entrambi i casi, è allineato esattamente sotto il [262] lato superiore della cornice. Anche le mani si corrispondono: la destra del papa imita, in modo invertito, il gesto della sinistra di Baruc; le altre due mani sembrano riflettersi l'ima nell'altra. Le similitudini sono tali che le mani dei due personaggi possono venire scambiate (TAV. 3).

(The Pope (Table 1) is designed according to the model of the prophet Baruch (Table 2): the same sitting position, with the body in front and side in three quarters, the same type of long coat, the features of the faces are very similar, especially the cutting of the beard and mustache, mouth, chin and nose. In addition, some differences show that one figure depends on the other: if, for example, the headpieces are of different species (a tiara for the pope, a cap for the Prophet), both are surmounted by a round button that in both cases is aligned exactly under the the upper side of the frame. Even the hands correspond to each other: the right of the Pope imitates, in reverse, the gesture of the left of Baruch, the other two hands appear to be reflected each in the other. The similarities are such that the hands of the two characters can be exchanged (Table 3).

Next, the Popess:

Anche la Papessa (TAV. 4) mostra un aspetto senza dubbio ripreso dalla serie di Baldini. In generale, la sua posa, l'essere seduta e di tre quarti, è simile a quella del profeta Abacuc (TAV. 5 sopra); tutti e due tengono un libro in grembo, e colpisce la similitudine delle braccia sinistre, vestite della stessa manica orlata che emerge da una„analoga falda del mantello. Alcuni particolari della Papessa si ritrovano in un'altra figura, quella della sibilla Libica, che condivide anche lei la stessa posa, con un libro nelle mani (TAV. 5 sotto). Ma questa volta le corrispondensee più notevoli appaiono dall'altro lato, alla sua destra, nel particolare della piega del mantello sotto la quale si rivela il libro aperto. Anche i tratti dei volti si somigliano: gli occhi cerchiati, le linee del naso e della bocca, la fossetta sul mento. Per di più, i copricapi, benché diversi, condividono la particolarità di essere conici e prolungati da un velo. Perciò la Papessa sembra_essere composta con il lato sinistro di Abacuc e il lato destro della sibilla Libica.

(The Popess (Table 4) also shows an aspect no doubt taken from the series by Baldini. In general, her pose, being seated and in three quarters, is similar to that of the prophet Habakkuk (Table 5 above), both hold a book in their lap, which affects the similarity of their left arms, dressed in the same hemmed sleeve that emerges from a similar flap of the coat. Some details of the Popess can be found in another figure, that of the Libyan Sibyl, who also shares the same pose, with a book in her hands (Table 5 below). But this time the most significant correspondences appear on the other side, to her right, in particular the fold of the mantle under which reveals her open book. Even the facial features are similar: the rimmed eyes, the lines of the nose and mouth, the dimple on the chin. Moreover, the headpieces, although different, share the distinction of being conical and extended further by a veil. Therefore, the Popess seems to be composed of the left side of Habakkuk and the right side of the Libyan Sibyl.)

It seems to me that the resemblance is clearly closer between the sibyl and the TdMII (left) than the TdM II (right). However the prophet might be closest to the Dodal TdMI.

The Emperor:

L'Imperatore (TAV. 6) sembra risultare dalla combinazione di due profeti. Da Eliseo riprende lo schema generale: la posizione seduta e la testa di profilo, ma anche il movimento delle braccia, i tratti del volto e il disegno dei capelli, in quanto un ricciolo è stato trasformato nella parte del copricapo che ricopre la tempia (TAV. 7 sopra). La spirale che si vede all'estremità della bandiera tenuta da Eliseo è stata riutilizzata nella stessa posizione, sotto la mano, come motivo decorativo sul bracciolo del seggio imperiale. Da un altro profeta, Giosuè, l'Imperatore riprende il viso, ma da questo bulino viene recuperato anche un elemento architettonico che orna il palazzo, il quale, un po' modificato, è divenuto la spalliera del trono (TAV. 7 sotto).

(The Emperor (Table 6) seems to result from the combination of two prophets.From Elisha the general pattern is taken: the sitting position and the head in profile, but also the movement of the arms, facial features and hair design, as a curl has been transformed into the part of the headgear that covers the temple (Table 7 above). The spiral that you see at the end of the banner held by Elisha has been reused in the same position under the hand, as a decorative motif on the arm of the imperial throne. From another prophet, Joshua, the Emperor has taken his face, but this burinhas also recovered an architectural element that adorns the palace, which, little changed, has become the back of the throne (Table 7 below).)

Next is Justice:

Nella Giustizia dei tarocchi (TAV. 8), il principale prestito dalla serie di Baldini è la postura della sibilla Eritrea: stessa posizione frontale, con una spada nella mano destra, il pomello tenuto sul ginocchio; simile il movimento del braccio sinistro, con la mano all'altezza del cuore (TAV. 9). Le due figure condividono anche alcuni particolari: il collare plissettato, l'arco della cintura, il movimento del drappeggio sulle gambe.

(In the tarot Justice (Table 8), the principal loan from the series by Baldini is the posture of the Eritrean Sibyl: the same frontal position, with a sword in her right hand, the knob held on the knee; similar is the movement of the left arm, with the hand at heart level (Table 9).The two figures also share some details: the pleated collar, the arc of the belt, the movement of the drapery on the legs.

Here the similarity is closest, I think to the TdMI.

Finally the Empress. In this case Poncet does not see a parallel with Baldini, but rather with an engraving by his master Finaguerra. However I think a case could be made for the Delphic sybil, which I include immediately above Poncet's TdMII Empress:

Se la figura dell'Imperatrice (TAV. 10) condivide un'aria di famiglia con alcune sibille, risulta difficile evidenziare prestiti precisi, mentre colpiscono di più le somiglianze con un niello, realizzato da Maso Finiguerra, orefice e incisore fiorentino maestro di Baldini (TAV. 11). L'immagine rap-[263] presenta una figura femminile seduta tra gli angeli, generalmente indicata dagli storici dell'arte come la Giustizia (Blum, 1950, p. xvii; Goldsmith Phillips, 1955, p. 13 e ivi la fig. IIA). La posizione generale è la stessa, il corpo frontale con la testa di tre quarti. I gesti delle braccia sono simili ma diversi sono gli oggetti tenuti in mano. Infatti, il disegnatore sembra aver giocato con gli elementi forniti dalla cosiddetta "Giustizia" per creare quelli dell'Imperatrice. Assembla dunque la spada e il globo della prima per formare lo scèttro della seconda, e reimpiega uno scudo presentato da due piccoli orsi, mettendolo sotto il braccio dell'Imperatrice. È anche da notare l'ovvia somiglianza tra i gesti delle mani. Stranamente, un'ala simile a quelle degli angeli del niello sporge sotto la coscia sinistra dell'Imperatrice.

La figura del niello è considerata una rappresentazione della Giustizia per le sue analogie con un quadro più tardo di Piero Pollaiolo che rappresenta questo stesso soggetto (Poletti, 2001, pp. 187-95); ma le similitudini formali non inducono necessariamente l'identità dei temi. Alcuni particolari del niello infatti si riflettono anche nell’ incisione della sibbìla Eritrea di Baldini (TAV. 9): la posizione generale, la plissettatura della camicia sotto la cintura, il movimento del drappeggio sulle gambe, il disegno delle nuvole sulle quali le figure femminili sono sedute. Inoltre, lo scudo del niello sorretto dagli orsi è quello degli Orsini, la famiglia del cardinale che aveva fatto raffigurare le dodici sibille. In un manoscritto che descrive la famosa serie dipinta nel suo palazzo romano, si legge che «il cardinale degli Orsini abbia fatto raffigurare un orso sotto i piedi della prima sibilla» Hélin, 1936, pp. 359-60). Se consideriamo questi indizi convergenti (orsi, scudo della famiglia Orsini, analogie con la sibilla di Baldini), possiamo supporre che il niello sia una prima testimonianza grafica della serie di figure che decorava il palazzo Orsini.

(If the figure of the Empress (Table 10) shares a family resemblance with some sibyls, it is difficult to highlight specific loans, while effecting more similarities with a niello made by Maso Finiguerra, Florentine goldsmith and engraver, Baldini’s master (Table 9). The image, generally indicated by art historians as Justice (Blum, 1950, p. xvii; Goldsmith Phillips, 1955, p. 13 and Fig. IIA there), repre-[263]sents a seated female figure between angels. The general position is the same, the body in front with the head in three quarters. The gestures of the arms are similar but there are different objects held in the hands. In fact, the designer seems to have played with the elements provided by the so-called "Justice" to create those of the Empress. He assembles, therefore, the sword and the globe of the first so as to form the scepter of the second and reuses into a shield what is presented by two little bears, putting it under the Empress’s arm. Also of note is the obvious similarity between the hand gestures. Strangely, a wing like those of the angels of the niello protrudes below the left thigh of the Empress:

The figure in niello is considered a representation of Justice, for its similarities with a clearer picture of the late Piero Pollaiuolo representing this same topic (Poletti, 2001, pp. 187-95), but the formal similarities do not necessarily lead to the identity of the subjects. Some details in fact of the niello are reflected also in the engraving of the Eritrean sibyl of Baldini (Table 9): the general position, the pleated blouse below the belt, the movement of the drapery on the legs, the design of the clouds on which the female figures are sitting. In addition, the shield of the niello supported by the bears is that of the Orsini, the family of the cardinal who had depicted the twelve sibyls. A manuscript that describes thefamous series of paintings in his palace in Rome states that “the cardinal Orsini depicted a bear under the feet of the first sibyl” (Hélin 1936, p. 359-60). If we consider these convergent indications (bears [orsi], shield of the Orsini family, analogies with the sibyl of Baldini), we can assume that the niello is a graphic testimony to the first series of figures that decorated the Palazzio Orsini.

I think the TdMII is closer to these engravings than the TdMI.

I think the TdMII is closer to these engravings than the TdMI.Finally, we should consider the relationship to the style of another group of cards, the ancestor of the TdM, as Dummett shows in his next chapter, namely the Cary Sheet, of c. 1500. Here are the relevant cards:

In their grace and charm, these cards are all very much in the style of the TdII. Especially look at Fortitude, a card not yet considered:

Poncet concludes:

II am not concerned with the rest of the essay, in which Poncet tries to connect the tarot with Ficino. But in what I have quoted, it seems to me that Poncet has demonstrated the visual similarities very well. I would not conclude that Baldini was the engraver of the TdM II cards, but rather that he or someone using his designs might well have been. The style remains Florentine of the 1470s, but that does not prevent a Florentine artist using copies of Baldini's work in Milan. So I see nothing to indicate anything stylistically later than Northern Italian c. 1500 or a little later for any of the TdM2 cards..La Papessa, il Papa, l'Imperatrice, l'Imperatore, la Giustizia: questi trionfi dei tarocchi di Marsiglia costituiscono dunque un insieme coerente; quanto all'aspetto formale, sono stati tutti disegnati nella medesima cerchia di incisori e gioiellieri fiorentini e risalgono agli anni sessanta del Quattrocento; quanto all'ispirazione, derivano da figure di profeti biblici e di sibille che illustrano concetti astrologici. Possiamo anche osservare che costituiscono due coppie: il Papa e la Papessa l'uno di fronte all'altra, mentre l'Imperatore e l'Imperatrice si guardano. Isolata è invece la Giustizia, che si presenta di prospetto. In apparenza, le sibille e i profeti sono stati raffigurati quali personaggi emblematici della società medievale e rinascimentale. Come vedremo la loro vera identità è tutt'altra.

(The Popess, the Pope, the Empress, the Emperor, Justice: these trumps of the Tarot of Marseilles, therefore, constitute a coherent whole. As to their formal aspect, they were all drawn in the same circle of engravers and goldsmiths in Florence and date back to the sixties of the 15th century; for inspiration they are derived from the figures of the biblical prophets and sibyls that illustrate astrological concepts. We can also observe which form two pairs: the Pope and the Popess facing one another, while the Emperor and Empress guard themselves. Instead, Justice is isolated, and she presents, in appearance, its prospect. The sibyls and prophets were depicted as emblematic of medieval and Renaissance society. As we will see their true identity is quite another.)

I also cannot see why the so-called "TdMII" is judged later than the "TdMI" (the Noblet etc.), other than the fact that the earliest surviving TdMII is later than the earliest surviving TdMII. But we really have no idea when these patterns were first implemented. The Baldini engravings look to me closer to TdMII. I don't see why they couldn't have been two variants that co-existed in Northern Italy by the early 16th century. From the primitiveness of the TdMI designs I do not conclude that it was earlier, but merely that the artist was less skilled, or perhaps wanted the cards to appear of a more ancient design than the other.

There is also the question of whether the Tarot de Marseille pattern might be even earlier than the 1460s. We know that the engravings of the Triumphs came considerably after similar depictions on cassoni. The model for Baldini's engravings of the prophets and sibyls was the series in the Orsini palace in Rome of shortly before 1432, which is where the 11th and 12th sibyls originate, via extant descriptions of them if not visual representations now lost. Zucker, in his discussion of the engravings (Illustrated Bartsch vol. 24 Part 1, p. 161), says:

This does not exclude, unfortunately, models that bear the same relationship to these engravings as the cassoni paintings do to the engraved Triumphs. Zucker notes that besides the Florentine style, Northern European models are also evident in "slightly less than half" of the engravings, "possibly French or Burgundian" and clearly German. This point, of course, needs to be kept in mind in relation to the Cary Sheet, too. My point is only that the style of the TdMII is as old as that of the TdMI.The majority of his figures are conceived entirely in the spirit of such contemporary Florentine painters as Verrocchio, the Polliauolo brothers, and the young Botticelli. Paintings executed by these artists ca. 1470-75 (e.g. the well-known panels of the "Seven Virtues" by Piero Pollaiuolo and Botticelli) seem to offer the nearest analogies to the engravings.

Hi, most interesting blog, great sleuthing.

ReplyDeleteI wonder whether you have any insights on this deck in the British Museum:

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?partid=1&assetid=1040185001&objectid=3236767

Does it seem like a precursor to the settled upon, Marseille design, or a later variant ? If it is an early one, some choices were yet to be made to add or take away certain details, which, to me, are significant. Note it is from Bologna.

Thanks for any musings you might be able to offer.

best - RB

That deck says "Francesco Berni" on the 2 of Cups. He was a cardmaker in Bologna 1770-1780, according to https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carte_da_gioco_italiane#Carte_lombarde_o_milanesi.

DeleteThis deck was discussed at http://forum.tarothistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=769

The deck is Marseille II in style, but with many departures. The titles indicate an ignorance of French grammar (La Imperatrice, etc.). The horses on the Chariot card are like those on Bolognese cards. Details on the Star card similarly. "Le Toille" is a detail first seen in Dodal, a Marseille I c. 1700. The horses on the Knights reflect Vieville, which is not a Marseille. Chairs tend to be less ambiguously wings. is like The Bateleur's table resembles those of the Lombard decks' cobbler a little later. Probably made for the Lombard/Piedmontese market.

I meant to delete the words "is like" in the 5th line above. Some other thoughts: Berti also did a 62 card Bolognese Tarocchino dated by Vitali to 1770 (http://www.letarot.it/page.aspx?id=233&lng=ITA). The British Museum does not seem to update its descriptions based on current knowledge. It is not to be relied on, except for what was thought by their authority at the time the dating was made.

DeleteThe deck is very similar to (but not the same as) the one that Vitali, http://www.letarot.it/page.aspx?id=233&lng=ITA, identifies as "Tarocco Lombardo, xilografie dipinte a mascherina [woodcuts painted by stencil] (Bologna, Al Mondo di David e Fratelli, 1780". To see examples of the cards, click on the title in bold, "Tarocco Lombardo".

DeleteOther examples of this type are linked to at http://forum.tarothistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=769&sid=8ab569bb50ee38fb740b60525217d452&start=10#p11215.

DeleteIt is amusing to see how the cardmaker has taken ambiguous suggestions in the Marseille II cards and made them unambiguous realities: the arm in back of the acolyte in the Pope card (on the right in, for example, Conver--but there it could also be a fold in the fabric), the back of the chair in the Empress card. Thanks for bringing this sub-style of deck to our attention.